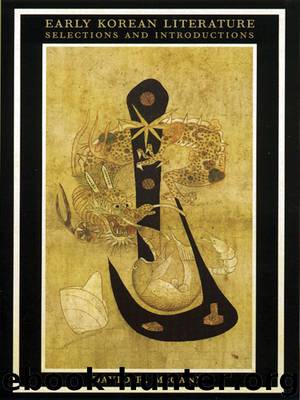

Early Korean Literature by McCann David;

Author:McCann, David;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: LIT008000, Literary Criticism/Asian/General, LCO004000, Literary Collections/Asian

Publisher: Columbia University Press

Published: 2000-09-06T16:00:00+00:00

NEGOTIATING LINGUISTIC MEANING

Just as various objects in the story become signs of the king’s, Ch’ŏyong’s, and others’ negotiated authorities, the events of the story give meaning, through narrative authority, to place names such as Port of Opening Clouds, to ceremonial dances such as the Frosty Beard Dance, and to locations that combine a narrative and ceremonial meaning such as the temple. In a less obvious way, the story also concerns itself with the question or issue of linguistic meaning in the exchanges between the king and the soothsayers regarding the fog, the meaning of the various spirits’ dances, and the meaning—adduced by the narrator—of the unusual words sung by the mountain spirit in its last-ditch effort to warn the court of the dangers approaching. Linguistic meaning in all these instances, like personal authority, is contingent, defined in terms of the events or conditions surrounding the word, the phrase, the building, the dance, the song.

The story is also about a different type of linguistic meaning, one that is less obviously contingent but is nevertheless negotiated, or bartered. A recently published concordance to the SGYS lists forty-four occurrences of the word mi, the Chinese character for beautiful; three of these occur in the story of Ch’ŏyong. (Eleven occur as part of the name of a Silla prince, Mihae, in Book I, the story of King Naemul.11) As we shall see, the meaning of the word is absolute in the sense that it is not defined by conditions or events but in fact defines conditions and instigates events.

The first instance of the word is adjectival, preceding woman, nyŏ, to make the phrase beautiful woman, wang i minyŏ ch’ŏ chi “the king by means of a beautiful woman wifed him” (Ch’ŏyong). The next instance of the word, immediately following, is as a verbal noun, ki ch’ŏ sim mi yŏksin hŭm mo chi pyŏnwi in “this wife so exceeded in beauty, the smallpox spirit adored her, changed into human form” (then went to her room at night and slept with her). Finally, after Ch’ŏyong has discovered the woman and the spirit in the bed, has danced and sung the song, the spirit resumes its true form, bows to Ch’ŏyong, and declares that because Ch’ŏyong has not displayed anger at what has happened, it “deeply feels and (holds) beautiful his action”: kam imi chi In acknowledgment of Ch’ŏyong’s restraint, the spirit promises never to enter a house that has even a likeness of Ch’ŏyong displayed on it.

In the story, to wife Ch’ŏyong is analogous to giving him a government office: it is a contractual arrangement, in exchange for which the king expects to keep Ch’ŏyong’s loyal service. We must infer that the woman has been chosen for her beauty, and thus pre-identified as a suitable offering to Ch’ŏyong, who is himself not human. Just as the house does not confine Ch’ŏyong, who habitually, we may again infer, goes out at night to celebrate in the bright moonlight, the marriage contract fails to confine the woman’s exceeding beauty, which catches the attention of the powerful spirit.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| African | Asian |

| Australia & Oceania | Canadian |

| Caribbean & Latin American | European |

| Jewish | Middle Eastern |

| Russian |

The Hating Game by Sally Thorne(18639)

The Universe of Us by Lang Leav(14807)

Sad Girls by Lang Leav(13886)

The Lover by Duras Marguerite(7575)

Smoke & Mirrors by Michael Faudet(5921)

The Rosie Project by Graeme Simsion(5812)

Big Little Lies by Liane Moriarty(5497)

The Shadow Of The Wind by Carlos Ruiz Zafón(5419)

The Poppy War by R. F. Kuang(5321)

Memories by Lang Leav(4559)

An Echo of Things to Come by James Islington(4539)

What Alice Forgot by Liane Moriarty(4420)

From Sand and Ash by Amy Harmon(4178)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(3802)

The Tattooist of Auschwitz by Heather Morris(3645)

Ficciones by Jorge Luis Borges(3349)

Guild Hunters Novels 1-4 by Nalini Singh(3235)

The Rosie Effect by Graeme Simsion(3194)

THE ONE YOU CANNOT HAVE by Shenoy Preeti(3151)